The other day my daughter came to me in tears. Her little brother had hit her in the head with a rock because she didn’t wait for him to finish getting his shoes on when it was time to leave for the school bus. She left him behind, which made him feel sad, and because he doesn’t have the emotional maturity and verbal agility to communicate his feelings to her, he demonstrated his hurt the way he knew how: by hurting her. She was physically unscathed but understandably in distress and I was concerned.

My children were experiencing two distinct attachment injuries from the same incident and the only way they were going to understand secure attachment was if they learned how to practice it themselves.

This wounded boy needed reassurance he was still loved while also understanding that what he did was wrong. It was okay that he felt abandoned, angry, and sad that his sister left him. It was not okay that he hit her.

This wounded girl needed to know that she doesn’t need to put up with people who would hurt her because they can’t figure out how to deal with and communicate their emotions. She had every right to be angry and decide not to give time and attention to someone who would hurt her.

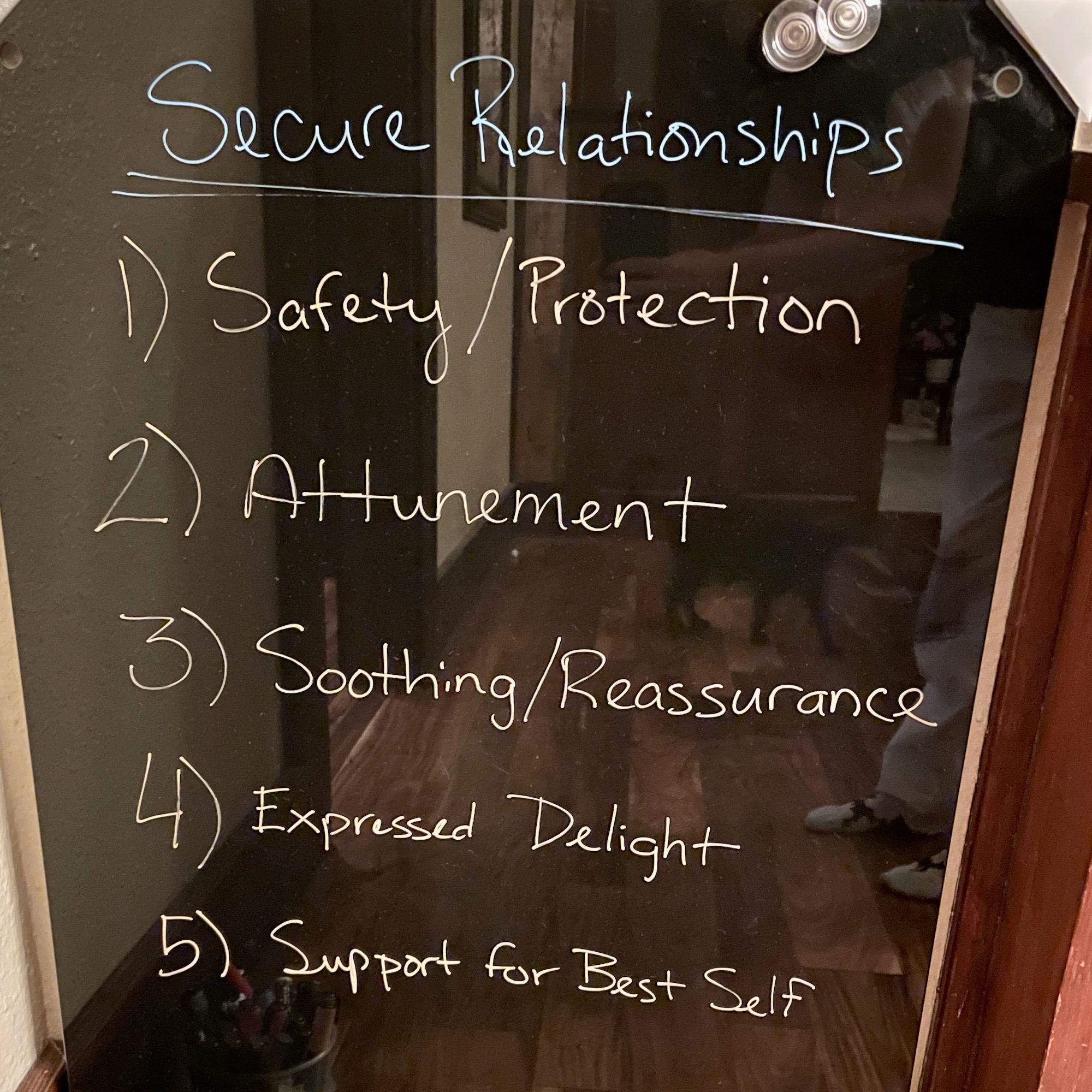

I’d been aware of Attachment Theory for quite some time, but only recently started to really dive into what makes and maintains secure attachments. I found the information so important that I wrote the five principles of secure attachment on the black board in our dining room and spent time going over them one by one with the kids.

Those academic exercises were about to take their first steps into my children’s lives.

I took them over to the black board and had them sit down.

Attachment Theory

I’d first heard about Attachment Theory 14 years ago when I was pregnant with my oldest. I was working at a parenting center where I could take all of the classes for free and one of the classes was on attachment parenting. When I wasn’t working I would also read several of the books in the library on Attachment Parenting by the likes of Dr Sears.

Years later it would come up again in a podcast I frequently listen to called Psychology In Seattle. The host, Dr. Kirk Honda, PsyD, LMFT, is an enormous proponent of Attachment Theory in his work and has done over 60 episodes featuring Attachment Theory (most of which I’ve listened to) including a six chapter deep dive I made sure to listen to twice so I could take more thorough notes (it’s that good). It was his last episode, however, wherein he talks about focusing on doing what it necessary to foster secure attachments that gave me the idea of attempting to pass that information to my children.

But it was The Attachment Project that gave me the last piece in the form of the five principles of secure attachments. The information presented there, along with the strengths and weaknesses of the different attachment styles was a significant step in understanding that attachment styles come with strengths and weaknesses and do not mean one is doomed to struggle. The site also has some great resources in discovering your own attachment style should you want to do so.

In a nutshell, Attachment Theory is the idea that the manner in which the needs of a child are met by a primary caregiver in infancy highly informs how that child will grow up to relate to the world and future relationships.

The two primary attachment styles are Secure and Insecure.

Secure attachments are formed when the physical and emotional needs of a child are immediately, compassionately, and appropriately met. When this happens, the child learns that he is worthy of care and people can be trusted as a source of love, nurutance, and safety.

If the child’s needs are not met, however, the child is forced to develop defense mechanisms that assume he or she is not worthy of care and others cannot be relied upon. This child may demonstrate one of the three Insecure attachment types: Avoidant, Preoccupied, or Disorganized.

This early-adopted attachment style may set the dominant tendency of that child’s future attachments but no one is only ever one attachment style. It may take time and energy, but insecurely attached individuals may learn to develop deeply rewarding and secure attachments. Likewise, a securely attached individual might experience trauma in life that leaves him fearful and avoidant of attachments in the future. Attachments may also fluctuate within a single relationship based upon the ebb and flow of the relationship itself and how the people within it interact and deal with stress and conflict.

And when an attachment is breached, the five things necessary for a secure attachment are a great place to start in both communicating the injury and the road to restitution.

The five principles of a secure attachment are:

- Feeling safe

- Feeling known and seen (attunement)

- Feeling comforted (soothing)

- Feeling valued (expressed delight)

- Support for best self

Communicating an Injury

I started with my son, as he was the one who struggled to communicate his feelings appropriately in the first place.

I asked him to point out the principle he felt was lacking when his sister left him behind.

He pointed to “Feeling safe.”

I asked my daughter to point to the principle she felt was violated when her brother hit her with a rock.

She also pointed to “Feeling safe.”

With a little help and guidance, I was able to get my son to tell his sister (with words this time) that being left alone at the house made him feel scared and sad and angry.

My daughter, already more verbally agile, was able to tell her brother that being hit with a rock also made her feel unsafe and angry.

Communicating Restitution

Having both successfully communicated the injuries, I asked them to point to what they felt they needed in order for the relationship to be restored.

My daughter pointed to “Feeling safe” and “Comfort.”

My son, on the other hand, didn’t point to anything. Instead, he shrugged and wrapped his arms around himself defiantly.

“Are you still angry that your sister left you alone?” I asked.

He nodded.

The Consequence

I thought for a moment.

Something I never want to do is invalidate the feelings my children are experiencing. Nor do I want them to feel as though they are being punished for their feelings. And no amount of punishment or discipline on my part was going to make him understand that what was really at stake here wasn’t whether or not he would get in trouble with me. What was at stake was his relationship with his sister.

“It’s okay that you’re angry,” I finally said. “I get it. I’d be angry, too. But you see, when you hit your sister instead of talking to her, you hurt her. Your sister has every right to decide that she doesn’t want to play with you if when you get angry you hit her. If she’s protecting herself, she should stay away from people who would hurt her like that. If you had told her you were hurt instead of hitting her she probably would have tried to comfort you, but instead, you hurt her. If you aren’t willing to comfort her and restore this relationship then she has no obligation to comfort you, either. It’s your choice.”

He shrugged again, and shook his head.

“Okay, then. I love you. I know your sister loves you, but it’s going to be up to you as to whether or not you want to restore your relationship with her. I think you should go upstairs and think about it a little bit.”

Tears started to build in his eyes as he sulked up the stairs.

I stayed in the dining room with my daughter to talk with her about boundaries and assure her that she was not responsible for her brother’s feelings, nor was she required to restore a relationship with anyone who showed no genuine remorse or behavioral changes after hurting her.

Restitution

It took a few hours, but eventually a little boy snuck down the stairs. He ran around the couch and threw himself into the arms of his sister where they cuddled and told each other they loved each other.

My goal in teaching attachment theory to my children is so that they can confidently identify and communicate their emotions in ways that do not cause attachment injuries. Once those emotions are communicated they can then identify and communicate the things they need in order to restore injured attachments. They will also be able to better understand whether or not someone is genuinely interested in repairing the breach versus distracting them with empty promises or platitudes.

In doing so I’m realizing that this exact same process can also be used for adults who are struggling to create and maintain secure relationships–especially if a baseline attachment style is already insecure.

It’s a work in progress, but I think I’ll leave the five principles of a secure attachment on the black board a little longer.

Or maybe I’ll find a more prominent place for them so that we can all use them to have closer and more secure relationships in our home.